Frank Faulkner was interviewed on October 4, 2021 by Patience Stuart and Kevin Taylor of AECOM for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' SM-1A Nuclear Reactor decommissioning project. The interview was conducted over the telephone with Frank at his home in Hapeville, Georgia, Patience in Portland, Oregon, and Kevin in Greensville, South Carolina. In this interview, Frank talks about working at the SM-1A nuclear power plant at Fort Greely, Alaska, arriving in Alaska in the winter, the training he received, and the challenges of the training and the job. He provides details of how the nuclear reactor functioned, day to day job activites, and the off duty activities of the SM-1A employees who were a close-knit group of people and families. He also talks about dealing with the cold, darkness and isolation at such a remote site and how it was more difficult for the wives who were stuck at home with the children. Frank also touches on other parts of his career, including time in Panama.

Frank Faulkner was interviewed on October 4, 2021 by Patience Stuart and Kevin Taylor of AECOM for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' SM-1A Nuclear Reactor decommissioning project. The interview was conducted over the telephone with Frank at his home in Hapeville, Georgia, Patience in Portland, Oregon, and Kevin in Greensville, South Carolina. In this interview, Frank talks about working at the SM-1A nuclear power plant at Fort Greely, Alaska, arriving in Alaska in the winter, the training he received, and the challenges of the training and the job. He provides details of how the nuclear reactor functioned, day to day job activites, and the off duty activities of the SM-1A employees who were a close-knit group of people and families. He also talks about dealing with the cold, darkness and isolation at such a remote site and how it was more difficult for the wives who were stuck at home with the children. Frank also touches on other parts of his career, including time in Panama.

Digital Asset Information

Project: Cold War in Alaska

Date of Interview: Oct 4, 2021

Narrator(s): Frank Faulkner

Interviewer(s): Patience Stuart, Kevin Taylor

Transcriber: Rev Transcription Services, Kelsey Tranel

After clicking play, click on a section to navigate the audio or video clip.

Sections

Introduction

Coming to work at the SM-1A nuclear power plant at Fort Greely, Alaska and driving to Alaska in the winter

Babies of military families being delivered in Fairbanks

Army's nuclear power training program at Fort Belvoir, Virginia

Similarities and differences between the SM-1 in Virginia and SM-1A in Alaska

Reactor recovery from scrams and startup, and working with civilians at SM-1A

Daily activity as shift supervisor, and electrical maintenance duties

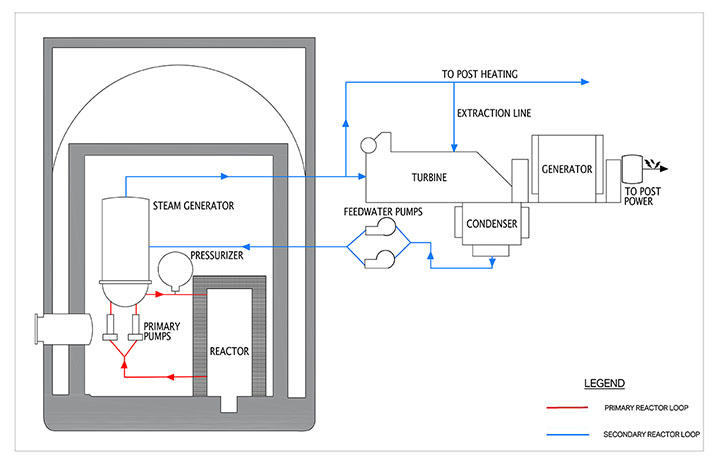

Description of how the nuclear reactor functioned to provide steam heat and electricity

Memories of interesting events with the generator and radiation contamination

Camaraderie and close-knit community of the SM-1A workers, and off-duty activities

Working in Panama after Alaska

SM-1A shutting down, and public opinion about nuclear power

Career after leaving SM-1A at Fort Greely

Things learned at SM0-1A that influenced rest of his life and career, and dealing with the cold temperatures

Steam generator exchange, and waste disposal

Effect of the isolation and cold at Fort Greely on the wives and children of military families

Conventional and nuclear power plant serving as backups during emergency

Seasonal swings in daylight in Alaska versus Panama

Qualifications required to enter the Army nuclear power program, and intensity of the training

Click play, then use Sections or Transcript to navigate the interview.

After clicking play, click a section of the transcript to navigate the audio or video clip.

Transcript

Patience Stuart: Alright. Today is October 4, 2021. This is an oral history interview with Frank Faulkner, and we are conducting this interview virtually, over the phone. We have two interviewers and one narrator. I am Patience Stuart. I'm a historian, and I am calling from Portland, Oregon. Kevin, we'll go to you next.

Kevin Taylor: This is Kevin Taylor. I am a nuclear engineer and health physicist, calling from Greenville, South Carolina.

Patience Stuart: And, then Frank, if you want to introduce yourself, and let us know where you're calling from.

Frank Faulkner: Sure, my name is Frank Faulkner, and I'm calling from -- interviewing from Hapeville, Georgia, which is a suburb of Atlanta.

Patience Stuart: Fantastic. Thank you. And then, as we record the interview on the website, what would you like -- how would you like your name represented?

Frank Faulkner: Frank Faulkner. That's my name of choice. My full legal name is Charles Franklin Faulkner, but almost no one -- I use Charles. I answer a phone. If they ask for Charles, I figure it's somebody who doesn't know me. So I then refer and say, "Charles isn't here, right now." So that's the way I screen my calls from telemarketers.

Patience Stuart: Sounds like a good approach. Well, we will use your name of choice, then, for the interview, Frank. And then would you prefer to be called Frank or Mr. Faulkner, today?

Frank Faulkner: Prefer what, please?

Patience Stuart: Frank or Mr. Faulkner?

Frank Faulkner: Mr. Faulkner was my dad. He owns the dog. So I'm Frank.

Patience Stuart: Okay, and then, Frank, what time frame did you work at SM-1A?

Frank Faulkner: Let's see. I arrived up there in '69, and left in '70. I was up there for a short period of time, during the steam generator exchange. And matter of fact, on -- I forget the exact date, now. I think it was May the 14th. And I was selected to go back to Purdue University to complete my electrical engineering degree. So, from January of '69 to August of '70, I guess it was. A relatively short period of time.

Patience Stuart: Do you recall your rank while you were there?

Frank Faulkner: I was a sergeant first class, E-7.

Patience Stuart: Okay. And how did you end up there? Tell us how you made your way to Alaska.

Frank Faulkner: How I made my way to what, please?

Patience Stuart: To Alaska. How did you end up at SM-1A?

Frank Faulkner: I was working at Fort Belvoir at the SM-1, I believe it was, at the time, and received orders for Alaska, and proceeded from Fort Belvoir to -- I drove all the way to Alaska. It was quite an experience in the wintertime. I think I left in late November and got to -- Well, it must have been early December -- and arrived in Alaska after a, I don't know, 3,000 mile or so road trip with four children -- four boys, and a pregnant wife, driving up the Alcan Highway in the olden days before it was paved.

From a point in Dawson Creek, Yukon Territory, I believe it was, right up to the Alaska border, it was gravel road all the way. But in the wintertime, it was nicely plowed, a nice smooth road. The problem we had was the road was white, the banks were white, and everything in front of you is white, so depth perception was quite difficult. But it was a nice smooth drive, and had no real problems getting up there.

And arrived in Alaska, I think it was a week or so before Christmas, arrived at my sister-in-law's house down in Anchorage and we spent Christmas there. And then right after the first of the year, I believe it was the second of January, we drove up from Anchorage to Fort Greely, and as I remember it was about 2 o’clock in the afternoon when we got to Fort Greely, already dark.

Checked in at the MP gate at Greely, and the MP there assured me, "Yeah, Sergeant Laur is your sponsor and he's got you all set up for a set of quarters." He gave us directions up to the place and he said, "Make sure you plug your car in tonight, it's going to get cold." You know, that was a kind of redundant statement. It was already 20 below zero, I don't know -- "It's going to get cold," he says. And it's already 20 below. So that was my introduction to Fort Greely.

Patience Stuart: And were you prepared to plug your car in?

Frank Faulkner: Oh yeah. I'd done all the prep work for that. I had the battery blanket, or placed a heater under the battery, and a blanket around the battery, and a dipstick heater to plug in the -- keep the oil warm. And circulating water heater to keep the engine coolant warmed up so it didn't get too cold. A small little electric heater to try to fend off some of the heat inside the -- fend off the cold inside there. So I was all prepared for it.

Kevin Taylor: Now Patience, I know we're going to get into some more technical things, and other personal comments, but before I forget, I wanted to ask Frank how his family felt that -- upon arrival at 20 degrees below zero.

We have a story from another SM-1A operator, whose wife was pregnant while he was there. And he told us a pretty unique story about his wife getting flown to Fairbanks for -- when it was time to have the baby. Could you tell us a little bit about what your family thought when they arrived, and how that new baby came while you were at Delta Junction?

Frank Faulkner: Well, we were excited about it. Oh boy, my boys were all -- They'd traveled around, we'd been in different places. In Virginia, there was a new program, and they were excited about going to Alaska and seeing some of their family that was up there.

My wife's sister was down in Anchorage. They were in the Air Force. So it wasn't a total surprise of the cold weather or anything else, so the boys were excited.

When you're 10 or 11 years old, everything's a new adventure. The oldest son, he was born in '61, so he would have been 10, 11 years old, I guess, when we got up there. So they were excited about a new adventure.

And the wife was pregnant, and the practice up there was that, I guess, about a week before your due date, the women would go to Fairbanks, for the best Army hospital. So that there was no sudden jolt of trying to dash off to the hospital for the baby's delivery that you see on TV all the time. But it was a week or so in advance, so it was a well-planned operation. The ladies went up to the hospital a week ahead of time, so that there was no crisis imminent at the baby's birth. And that was pretty much straightforward. It ends up that I had four sons, and the latest addition was a daughter. She was born in Alaska, so she was our Alaska angel.

Patience Stuart: Sounds like all --

Frank Faulkner: We had kids born in Indiana, Ohio, state of Washington, and in -- I'm trying to remember which one was born -- And Virginia, and then Alaska. So I had kids born all over.

Patience Stuart: Sounds like a well-rounded group.

Frank Faulkner: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, good group, good bunch. And they're all equally scattered out now: Wisconsin, Texas, New Hampshire, here in Georgia. They're scattered all over.

Patience Stuart: Well, I'd like to back up a little bit. And so, you mentioned that you had been an operator at SM-1 at Fort Belvoir. Did you go through the training program there, as well? Frank Faulkner: Yes. Patience Stuart: Okay.

Frank Faulkner: I was in class 64-2. That was the first class after the -- At the SM-1, the first class after the HP mod was put in. And I'm sure if you're familiar with the SM-1, during its demolition, the HP mod was the area where you went into containment out of the HP mod.

But the plant was all shut down during that period of time, and the classes were then conducted after the plant came back up. So I was in the first class after the plant, the SM-1, came back online in '64.

So I showed up in August of '64. I'm sorry, December of '64, and started class then at the SM-1, and went through the training program and the year's training there, and then the 16-week specialty training for electrical.

And I ended up being the electrical supervisor, the maintenance supervisor, during one period of time there, and the shift supervisor at the SM-1. And the same sequence of duty assignments as the SM-1A, electrical maintenance supervisor, and the shift supervisor there at the SM-1A.

Patience Stuart: Just for the purpose of the recording, could you define HP for the HP mod?

Frank Faulkner: Yeah, Health Physics. Patience Stuart: Okay.

Frank Faulkner: That was the area for the -- Where the predominant radiological parts of the HP program were done, in the HP mod.

Patience Stuart: I see.

Frank Faulkner: Yeah, anything that involved radioactive materials, it was done in that new modification.

Patience Stuart: I see. So you had training and then you were an operator at SM-1. Was there additional orientation, or was the training any different once you arrived at SM-1A?

Frank Faulkner: It was a familiarization. They were quote "sister plants." There were some differences, but they were minor. The biggest one that you really noticed was the condenser on the turbine.

The condenser at the SM-1 in Virginia was a huge, big appendage hanging below the turbine, and it took the exhaust steam and mixed it back to liquid, and that was your secondary water. At the SM-1A, the condenser was -- The first thing I thought of was just a 55-gallon drum, it was so small.

Two reasons for that was the SM-1 was using Potomac River water as the coolant for the condenser, and the SM-1A was well water, which was right at 40 degrees year round, that went into the condenser.

And the second reason was, a large portion of the steam at SM-1A in Alaska was used in post heating. So we would take the -- I think it was seven stage extraction that was pulled off of the turbine and sent off to post for post heating. So we used essentially the post as part of our condenser. We didn't need a big condenser like we had at the SM-1 in Virginia.

And temperature of the coolant going in the condenser was vastly different in the two spots. That was the major difference.

The reactors were very similar, the pressure vessels and everything like that. You had the same sort of primary loops, the secondary makeup pumps and all of that were in different locations but it was still the same basic principle. The layout was different, but the design was -- or the function, was the same in the plants.

That was a big difference, was the steam was being used for post heating at the SM-1A in Alaska, and at the SM-1 in Virginia, it was being recycled all the way. Had a tremendous amount of losses, condensate, out through post heating. You could tell where it was -- the leaks were out there, because the grass was green, even in the early spring the grass was green because all the steam being condensed and condensate loss there.

Kevin Taylor: Were you aware of any radiological issues that evolved from the post heating system with the steam?

Frank Faulkner: No, it was all secondary water. Kevin Taylor: Okay.

Frank Faulkner: And nothing went in the primary. The only -- There was no physical contact between the primary loop and the secondary, except in the steam generator itself. The primary water was on one side of the tubes, and the secondary water was on the other side of those tubes. So, that was the only place that you could’ve had contact. And if you had a leak between the tubes, you could have had some contamination, but that was, as far as I know, that was never an incident or never a problem.

Patience Stuart: I see.

Kevin Taylor: Great, thank you.

Patience Stuart: Frank, could you describe a typical day in your role as both the shift supervisor and also as the electrical maintenance supervisor?

Frank Faulkner: Well, the big difference, of course -- Whoops. Got a -- One of my tenants is sending me a voicemail message. Okay, I don't know if you can hear the noise or music in the background where he's recording a message for me. That's an aside from our interview.

Patience Stuart: Sure. We can't hear it, it's fine.

Frank Faulkner: Oh, okay, very good. The role was nearly identical in both the SM-1 and the SM-1A, that either the electrical supervisor's job or the shift supervisor. Now when you got to Alaska, the big thing you noticed up there was that you had a number of civilians. You had two civilians, I want to say a number, two civilians, that were former nukes that had retired in Alaska and worked on the plant there, and they were both shift supervisors.

They had gotten so far out of practice because the plant SM-1A in Alaska was an operating nuclear power plant that was designed to go online and just supply power, whereas the SM-1 was a training plant, and you were constantly practicing recoveries from scrams, or problems.

At the SM-1A, you didn't want problems, and you had no practice at recovering. So that was the thing that the two guys that retired up there, that were civilians who had been former nukes, they had gotten so far out of practice at making recoveries from scrams, that they always had to make a startup basically.

There was no -- well again, recoveries like you had at the SM-1, because you practiced all the time of scram recoveries at the SM-1 in Virginia, and you didn't have that practice at the SM-1A.

Now the drill was the same in both places, but it was just a matter of reaction time and how quickly you could get it back up, and go from there. Of course, the SM-1A was -- after we had the steam generator exchange and refueling, that core was much faster operating than the one in Virginia was.

Patience Stuart: Did the plant -- did it shut down frequently, or were these also drills?

Frank Faulkner: Oh, the one in Virginia, that was --

Patience Stuart: Was drills. But --

Frank Faulkner: You had two or three scrams a night, or a shift, just practicing. But the one in Alaska, it was a power plant steady state operation. Your goal was not to shut down.

Patience Stuart: Okay, great. Did it still happen every so often though?

Frank Faulkner: Well, occasionally it would occur, but it was not near the frequency you had --

A scram at the SM-1A in Alaska was an event that everybody knew about, and everybody was, you know -- it was not a common occurrence as it was in Virginia. So it was kind of a --

that's what delayed, you know -- the reason that it was not a rapid recovery there was because -- (coughs) Excuse me. Was that it was not an everyday occurrence. You might get a scram once every month or so. But if you didn't happen to be on shift when that occurred, you didn't see one for 3, 4, 5 months occur. The goal was not to shut down but to keep it going.

Patience Stuart: So what were some of the daily activities that you would go through as a supervisor?

Frank Faulkner: As a shift supervisor, it was just making sure that -- the same drill at either plant, that you would come in, half an hour before your shift is scheduled to start, you would walk through the plant, check things out, see what was operating, go up the control room, read the logbook, and see what had occurred since the last time you were on shift.

And then you would get briefed by the operator you were replacing, and then go over anything that had occurred, review the clearances and caution orders, equipment that was tagged out and out of service. Each operator did that, the equipment operator, the control room operator, and a shift supervisor would go through the exact same drills, or routine, of walking through the plant, checking what was operating, what was going on, anything new happening, read the logbooks, see what there was, and then get briefed by the operator you were replacing. So it was a routine shift change, and that occurred at either the plant in Virginia or the plant in Alaska.

Patience Stuart: Were there additional tasks tied to your role in electrical maintenance?

Frank Faulkner: I'm sorry, was there was what? Difference in the role?

Patience Stuart: Were there additional tasks tied to your electrical maintenance role?

Frank Faulkner: No, no. Between the two plants, it was identical. You just dealt with the problems that were there, and made sure that you got the right folks assigned. You had your crew in the department, you issued a -- checked the work orders out, and you issued those out.

There was very little maintenance done on the second and third shift, predominate maintenance was done on the day shift. So the maintenance personnel were basically day shift personnel.

Patience Stuart: I see.

Frank Faulkner: So that was in both plants.

Patience Stuart: Gotcha. We've heard a lot of experiences from operators about their day-to-day, and their experiences, but I'm not sure if we have recorded just an overall summary of the primary and secondary loops. Would you feel comfortable just explaining on the recording how the reactor worked?

Frank Faulkner: Well, okay. I'll make an attempt. It's been a bunch of years since I laid hands on a nuclear reactor. Patience Stuart: Sure.

Frank Faulkner: But I'll try to dig it up from my memory. The primary loop was the water that went from the (generator) into the reactor itself, entered the core, passed through the core and picked up, let's see, about 40 degrees I think delta T across the reactor.

And then it went into the steam generator, gave up the heat in the steam generator, out of the primary loop, into the secondary loop, and sent the pressurized steam out on the secondary steam loop to the turbine. And there it was condensed back to just water, picked up from the hot well on the condenser.

The water was then pumped back into the loop again. The primary loop was all inside the containment vessel, and the secondary loop would make a penetration into the containment, to go into the steam generator, and the steam came out to the turbine, condensed secondary water back in again. So it was two closed loops.

The primary loop was all inside the containment, and the secondary loop was in the containment, back out. In as water, out as steam, and pumped back into the secondary. The two, primary and secondary loops, never mixed, so you had no interchange of primary reactor -- primary water with the secondary water. Busy day, yeah. Got another call here. Did that answer your question? It's a very, very simple explanation.

Patience Stuart: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, you provided -- I didn't mean to put you on the spot, but you provided a really great explanation, and I think it's just good that we have it recorded, as well. So thanks for doing that.

Do you have any memories or stories of events or any interesting instances that happened at SM-1A during any of your shifts? Any discoveries or events?

Frank Faulkner: Well, a couple things stand out. One of the things that -- after we brought the plant back up, after the steam generator exchange, was we cleaned the electrical generator. During that period of time, we had taken the soldered solvent and washed out all the windings and everything in the generator.

And I remember the day we fired it up, it looked like a pillow had exploded out there on the turbine deck from all the dust that had been collected inside the -- dust and lint and things like that, inside the generator windings. That when we fired it up, there was no binding to hold it in there. All the oils and things that were there had been washed out, and now the generator, when it started turning, it's like a big pillow fight with all the little fuzzies in the air. That was one thing that was neat about it.

Let's see, another neat, interesting I remember was, we had our OIC, a Major Dorr, he'd gotten -- some way gotten contaminated in the plant, and he had to change all of his clothes out. He didn't have the -- He wasn't in the containment vessel, he was some way or the other he had gotten contaminated outside of containment, either a primary sample point or something.

But anyway, he'd gotten contaminated, and his wife had to bring him a fresh set of clothes. And she was pregnant at the time, and she was standing outside the fence, throwing clothes over the fence to her husband who was standing there in his coveralls that he was wearing. His uniform had gotten contaminated. That was a memory that I had there.

It was a close-knit group, that was the thing about both plants. The one in Alaska was far more close-knit than the one in Virginia, because we were stuck 100 miles from Fairbanks, and 300 miles from Anchorage. Not much going on except our relationship with each other, and a very small military community that we didn't really get too involved with.

Our job was to run the power plant and we had no real other time, so our assignment group, our group of family and friends, were all nuke plants, nuke power plants. So we'd have our little parties and things, but it was all a very close-knit group that we had up there. And it was, like I say, a very close-knit group.

Patience Stuart: We have definitely heard that across the board. I think everyone really enjoyed their time there. Could you tell us some of your off-duty experiences? What all did you guys do together?

Frank Faulkner: Could you say that again? You were breaking up.

Patience Stuart: Sure. Tell us a little bit about what you did off-duty with your colleagues. What sort of things did you do together when you weren't working?

Frank Faulkner: Well, we'd visit with different families, we had get togethers. Like BJ, you interviewed him I believe, his wife was the Scout master. So our oldest son, he belonged to her Cub Scout troop, so that was an interesting operation there.

Then we would have group parties out at the Rod and Gun Club. We had get togethers of just between families, you know, families meeting with families.

Doug McCarty, I don't know if you interviewed him or not, he got out of the program after he left Alaska. But he and I, we'd go up hunting. Or K.O. Rafferty, he was another sergeant first class, we used to go out rabbit hunting after shift, especially afternoon shift, on second shift. We'd get off at midnight, during the summer it was daylight so we'd go off and shoot bunny rabbits and bring home bunny rabbits.

Or moose hunting season, a couple or three of us would go out at a time and hunt moose. Fishing, fishing was great up there. Just a small town, a very small group of folks, basically doing the same things you'd do here except it was hunting and fishing up there. The ladies would get together during different activities.

Patience Stuart: Sounds like a great --

Kevin Taylor: Frank, we've spoken to a few folks that were up there that are still in Alaska. Did you have any desire to stay in Alaska or return for permanent residence up there?

Frank Faulkner: Not really. I left Alaska in the summer of '70 and went back to Purdue University for degree completion. During that period of time, I was in school was when the decision was made to shut the plant down, and not keep it going. So I had no real opportunity to go back up there. I worked in engineering division for a while, then I went to Panama from there to the power plant, a fossil fuel plant in Panama.

So I never had real desire. Now a lot of the -- I won't say a lot, but a number of the guys did retire up there. Let's see, Bill Prestridge retired up there. Norm Gehring retired up there. There were two or three others that retired and stayed in Alaska, working for the power plant there. They were to a point they probably just retired up there, and lived the good life in Alaska.

Patience Stuart: Yeah. Do you remember the conversation, or the messaging about SM-1A closing? Do you remember how that information was shared or what the reasoning was?

Frank Faulkner: Not -- You know, it's what, 30 years ago now? Yeah. My memory's pretty good except it's so short now. On that case. I remember that, I think I was working in engineering division at that time, that it was decided to shut it down, it was just not -- well, I guess economically feasible to keep it going because it was going to require some major structure changes on steam line containment, steam line bracing, and a number of other things. It just was not practical or economical I guess to continue it.

Quite honestly, I'm not real sure that I ever knew exactly what prompted shutting down the plant totally.

Patience Stuart: I see. Do you remember much about the popular opinion around nuclear power at the time? Or what did your family and friends think about you working at a power plant, a nuclear power plant?

Frank Faulkner: Well, there was no particularly, decision -- Nobody was adamantly opposed to nuclear power. They weren't the things that automatically thought of nuclear power being atomic bombs, and I was doing that, you know, a dangerous job. But it was just a --

Yeah, there was no particular thought one way or the other about the philosophy of nuclear power. Which, I was a proponent of nuclear power, and I still think we're going to have to end up going back to it. If you want to get rid of all the problems or the carbon pollution in the air, you're going to have to find out some way to make electricity without fossil fuels, and nuclear is the logical choice. In my opinion, anyway. The sun doesn't shine all the time and the wind doesn't blow all the time. Patience Stuart: Yeah.

Frank Faulkner: After you've got rid of wind and sun, the cleanest one left is nuclear power.

Patience Stuart: Right. You mentioned that you went down to Panama after your time at SM-1A, and then back at Purdue. Were you involved with the Sturgis at all?

Frank Faulkner: No, as a matter of fact, the only time I was ever on the Sturgis was just over as a visitor one time. But I was never assigned to the Sturgis, and never operated at all, either case.

My story was the folks over -- assigned at the Sturgis, they were on the Atlantic side, and I had the plant over on the Pacific side, and I told them they were always very lucky that they were assigned over on the Atlantic side. The story was, "Why is that?" And I said, "Well, you're over on the Atlantic side and you've got someplace to go. I'm over on the Pacific side and I'm already there." I didn't have any place to go, so they had a place to go.

But yeah, that's, yeah, a little joke about Colón, Panama and being a smaller operation, and I was over on the Pacific side where I had Panama City right there.

Patience Stuart: Sure, they were on the quiet side. Could you tell us a little bit more about your career after the nuclear power program?

Frank Faulkner: Let's see, after I left Panama, came up to -- I was offered a choice of four assignments. I could go back to Fort Belvoir, and I said, “Well, I've been there.” I was offered the choice of Presidio, San Francisco to start the unit up out there, and I said, “I couldn't afford San Francisco cost of living.” And I had a choice of Fort Hood, Texas, and I said, “No, no, I don't need any desert.” And the wife and I had been to Atlanta earlier, and she enjoyed Atlanta very much, so that was my choice.

So I started the facility engineer support agency group here in Atlanta. I had a team over at Fort Benning, one at Fort Knox, one over at -- What the hell is the post over in Carolina? And the one here at Fort Gillem here in Georgia. So that was my duty here, we just operated in a support agency for the post engineers basically, and worked at other parts around the world.

From our group here in Atlanta, we had a team that went back to Panama to work down there at the supporting post engineers, surveying -- infrared survey of the electrical distribution lines. We sent a team down to Guyana for AID to help them get their diesel generators back up running. And that was a tri-service, or tri-nation operation.

We had a team from the U.S. working on the diesel generators, and we worked in coordination with the Canadians who were installing a new diesel generator plant, and the British who were working on the Guyanese to keep their steam generator plants up and running.

We supported deployment of some diesel generators to Saudi Arabia and various places around the world like that. Puerto Rico, we worked down there with the post engineers at Fort Buchanan. Of course, all the posts in the southeastern part of the United States, here in Atlanta.

Let's see, while I was in Panama, I was promoted to master sergeant, E-8, down there at the power barge, Weber. And then when I got back up to Atlanta here, I was promoted to sergeant major up here. That's about the end of my career.

They offered me a -- The Army said I had to leave the program. I said, "Well, what do I want to leave the program for?" They said, "Well, you're a sergeant major now, we need you to go down and be a National Guard advisor to the Louisiana National Guard." I said, "Well, no, I think I choose to quit," so I did.

Patience Stuart: Could you tell us about anything you learned or experienced at SM-1A that influenced the rest of your career with the facility engineer support group?

Frank Faulkner: Well, it was -- if you were fairly isolated up there and you had to make a lot of planning to make sure that you had what you needed to keep the plant running. You had to be -- Basically, you didn't have the luxury of running off to the hardware store and getting something if you didn't have it on site. So you were much, more self-sufficient up there, and I guess that was one of the things that you developed at an isolated point like that.

But you were trained to do that, because our plants were basically going to be isolated. The Navy had the plant down in Antarctica, and there was no running off to the hardware store from down there for parts. And same thing in Alaska, that, you know, you had to have the parts on hand or you had to improvise, or get them shipped out to you.

That occurred during -- That was another instance of during the steam generator exchange, we ended up short a lot of steel that needed to go in for supports on different parts, that had not been programmed into it. So they had to fly it up to us in the wintertime, on a C-130. That was another drill, 40 below zero, 30, 40 below zero, you're unloading steel off of an airplane, and they kept one engine running, a big fan out there blowing sub-zero air across the -- through the aircraft as you were unloading steel and taking it back to the plant. So that was another one of those things you remember, how cold that big old fan was making that cold air blow.

Patience Stuart: Right, gotcha. Could you explain what happened -- what was the steam generator exchange? Could you just tell us about that event?

Frank Faulkner: I'm not sure what prompted the requirement for it. I'm sure it was a problem of the steam generator itself was failing. I never learned or even had a discussion of why it was being exchanged, but it had to be removed and taken out.

Now this was a fairly large piece of equipment that had to fit through, I think it was about a 6 foot diameter entrance into the containment. So it had to be disassembled, and pulled out, and taken out through there, and then the new one brought in and installed in the same direction.

Even with all the decay heat, the containment vessel was quite warm, thermally warm, and then you had the radiation in there of all the exposed piping that was radioactive. So you had radiation that you had to contend with, which would limit the stay time of personnel, and then just the heat of exhaustion from the sweating, if you would.

But why it had to be exchanged, pulled out, I don't know, but I'm sure it was quite a reason for it. A failure of the unit itself, because it was not a small undertaking.

But that was -- as the story goes, above my pay grade of why that was -- I was a sergeant at the time, and that decision was made by the engineers.

Kevin Taylor: Were there any other major operations that took place while you were there? Core replacements, spent fuel shipments, anything like that, that you recall?

Frank Faulkner: Not that I recall. Waste disposal was something, but that was all handled by the HPs. And as an electrician and an operator, I never got involved in the waste disposal or anything like that. I'm sure the core was --

Kevin Taylor: I'm sorry, go ahead. I'm sorry, Frank.

Frank Faulkner: I don't even remember if we had to -- a spent core in the spent fuel pit or not. I know they obviously had to pull the fuel out and ship it out when they decided to shut the plant down, but I wasn't involved in it. I'd already come back to Purdue at that time, that decision was made.

Kevin Taylor: As an electrician, would it surprise you that some of the original switchgear is still in use by the current utility operator on base?

Frank Faulkner: Nope, not at all, not at all. That was one thing that we prided ourself in was maintaining our equipment. So it was -- We didn't have any Federal Pacific equipment up there, the only -- I don't know if you're familiar with that particular brand, but that was not a great brand of equipment to have. Switchgear. But I'm not surprised that some of the original switchgear was still there.

Patience Stuart: Kevin, do you have any more technical questions?

Kevin Taylor: I do not, Patience.

Patience Stuart: Frank, do you have any other memories that you'd like to share? Or memorable experiences from Alaska or SM-1A?

Frank Faulkner: Well, it was just a novel situation being up there. Essentially, you're isolated. It was much harder on the women than it was on the men. We got to go to work every day and come home. The women had a much tougher time, because during the winter it was 30, 40 below zero. Couldn't go outside and play with the kids.

Our set of quarters backed up to the school, which was probably maybe 500 yards from the house, but in the wintertime, the kids couldn't walk to school. They had to either ride the school bus or take the Army transport, depending on what the temperature was.

When it got to, I think it was 20 below zero, that the school buses wouldn't run, but they had to take Army transportation, which had better heating for the kids to ride in the military vehicles.

But in the summertime and spring when the snow was gone, the kids could walk to school, but in the wintertime they had to take the vehicles, they couldn't walk because of the temperature.

It's the same thing when -- that -- that was the problem with the women getting basically isolated into the house with the kids. So it was much tougher on the women, because the men would go to work. We had our routine there, and go home and there the wife would have been there all day with the kids, and then it was much more difficult for them than it was the men.

That's the biggest thing that I think about the problems, social problems if you would, on the power plant operation up there, was the isolation for the women. And that's the reason you'd have your little get togethers within the group, they were suffering. I guess all the military spouses were suffering the same problem, but we had our own little tight group that we dealt with.

Patience Stuart: Yes, I can --

Frank Faulkner: We were pretty aware of those --

Patience Stuart: I can definitely picture and imagine the cabin fever that must be felt, not only being in an isolated space but also being stuck inside 'cause of the weather.

Frank Faulkner: Right. And the thing of supplies that the commissary, where you got your food, all that stuff was -- They would have shortages. You would get down there and you'd stock up.

When you left post during the wintertime, you never left without -- If you're going up to Fairbanks, you had all your winter clothes and everything in the car, you had food in the car. You just had to plan differently for the life up there, and that was one thing that occurred.

Every house had their own supply. We had C-rations, military rations, that came part of your house. You had to keep those there in the event of a problem.

Now, I don't know how true it was, but I heard that, if both power plants, if the nuke plant and the conventional power plant went down in the wintertime, there was a 4 hour window that they had to be back up online or literally they had to evacuate the post, because it was going to get cold and there was no way to keep the places warm. So that was another thing that you had to make sure of, and worried about up there.

But it was interesting. Would I do it again? Probably.

Patience Stuart: Sense of adventure, yeah. You had mentioned -- you had talked about the steam, the condensed steam, being partitioned off for post heating. Was there always enough heat when it was running?

Frank Faulkner: Oh yeah, oh yeah. There was -- We never had to worry about post heating steam, we always had enough of that. Then the plant right next door, the fossil fuel plant, they had the capacity to -- when we were down for the steam generator exchange, then they supplied the post heating steam.

That plant was designed to support the heat for the post before the nuclear plant was installed. So we had the cross connection between the two plants of either one of us could supply post heating with no problem. We had sufficient from the new plant or from the fossil fuel plant to supply sufficient power, or sufficient steam, for the post heating.

Patience Stuart: Thanks for explaining that. Well, I think we're close to wrapping up, but happy to stay on if there are any other stories you'd like to share.

Frank Faulkner: No, not particularly. It's just that -- I think back there was a lot of good times up there, and then there were some miserable times. But other than that, it was quite an experience.

The exact opposite when I went to Panama, there you never had a freezing day. Like I say, when I reported in to Fort Greely, it was on January the second or third, and 2 o’clock in the afternoon it was already pitch black and 20 below zero or so. In Panama, it was daylight all the time down there, yeah, 12 hours a day daylight basically.

Alaska, the days changed by 6 minutes every day. You had 6 minutes less or 6 minutes more of daylight depending on if it was approaching the longest day of the year or the shortest day of the year. And it changed by 6 minutes a day.

Conversely in Panama, it's basically 12 hours one way or the other, 6:15 or so in the morning it gets daylight, 6:15 in the afternoon it got dark in Panama. But in Alaska, it was 6 minutes a day changing. Every day was 6 minutes difference from the day before. So that was something you had to get used to.

Patience Stuart: That's quite drastic.

Frank Faulkner: Yep. And in the summertime there in Alaska, you had to literally put tinfoil or aluminum foil in the windows so that you could get some dark -- the kids could go to bed. You know, at midnight, it's still the sun's up and it's daylight, kids want to go out and play. "Well, wait a minute there kiddo, it's bedtime." "Well, it's daylight." "No, no, it's bedtime, time to go to bed." So you had to literally darken the rooms, even the room darkening drapes and things weren't sufficient, so we would tape aluminum foil in the windows in the summertime to make it dark so the kids could go to bed. Difference in operations, on an --

Patience Stuart: Sure. Frank Faulkner: -- isolated post like that. And the swings in temperature, and the swings in timing, daylight.

Patience Stuart: Absolutely. Kevin, anything else from you?

Kevin Taylor: Nothing on my end.

Patience Stuart: Okay. Well, Frank, thank you so much for your time today, for doing this interview. And thank you for your service to the Army Nuclear Power Program, and for your time at SM-1A.

Frank Faulkner: Well, it's very good. It's been a pleasure. I can't think of anything I would have done in the military that would have been more fulfilling than working in the power plants. I don't know if you've talked to any of the other guys, but --

And the qualifications that we had to have to go into the program were extremely stringent. You had to have, on the military aptitude test and everything, you had to have a minimum of 115 on your GT score, which was kind of the rough equivalent of the IQ. You had to have that. That was the highest of anything in the military schooling to get to that. Then you had the intense training that you went through.

I don't know if anybody mentioned it to you, but the first thing we did when we went to school and showed up for class, we had to take the Evelyn Wood’s speed-reading course, because you were going to get bombarded for 8 hours a day with information. Then you had your homework to do at night, and then you go back the next day for essentially 8 hours of lecture again. So it was information was coming at you hard and fast during the school.

And the attrition rate was something like 30 percent or more at the school, because it was so intense, the instruction. But you had --

Everybody that was there was used to being number one in your class at anything they went to. And then you got to nuke power program, everybody had been number one, so now you got a competition there of folks who were all successful, and then now you're competing with everybody else who had been successful. So it was quite a change from most military schools you went to. The nuclear power program was very intense. Patience Stuart: Wow.

Frank Faulkner: And fulfilling, too.

Patience Stuart: Hm, mm. What a specialized group.

Frank Faulkner: Oh yeah, weird too, that's what the wife says. "Y'all are all strange. You're a weird bunch." And we agreed, yes, that's what made us special. We were all weird and enjoyed the competition. But I like to think we were all very intelligent, and had a good time competing with one another.

But, anyway, thank you for the opportunity for sharing some memories. Dredged up some I hadn't thought about for years.

Patience Stuart: Well, it's definitely been our pleasure talking with you, so thank you again.

Frank Faulkner: Alright.

Patience Stuart: All right, I'll go ahead and -- Kevin Taylor: Yeah, thank you, Frank. Patience Stuart: -- conclude the interview now.